The geological history of Boutenac...

… In the space of a video clip

From the Jurassic to the Quaternary Period, the soils of Boutenac are marked by 203 million years of complex geological history – summed up in just 203 seconds.

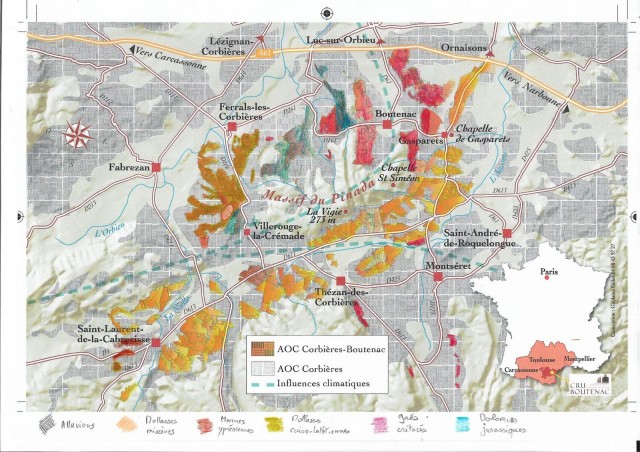

Although Cru Boutenac cannot be reduced to the vineyards that follow the pebble-strewn hillocks of Gasparets, the landscape with Saint-Martin’s chapel as its delicate centrepiece is often considered as the appellation’s most symbolic site.

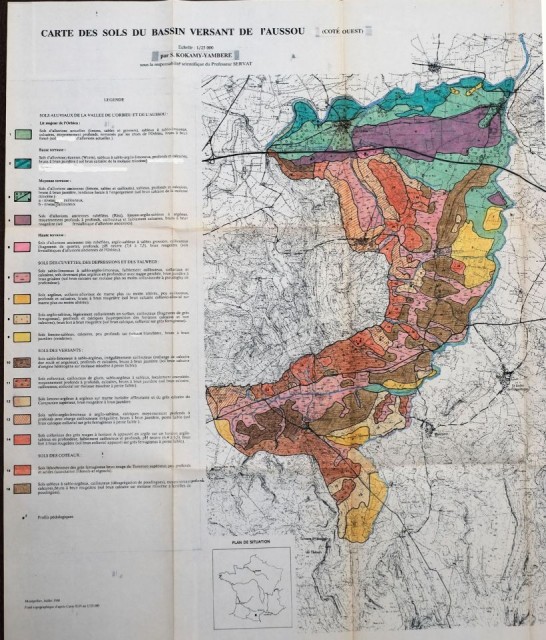

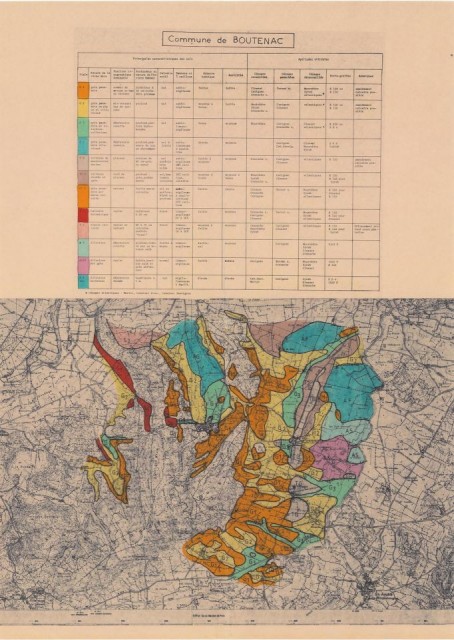

Picturesque scenery, though, is not the only defining feature here. Experts from Inao (National Institute of Appellations of Origin), tasked with establishing precise boundaries for the appellation area at the beginning of the 2000s, clearly felt that the Miocene molasse – the name given by geologists to this wide strip of pebble-rich soil, sometimes a hundred metres thick – “forms magnificent substrates where stone content and the fine fraction are in harmonious balance, providing vines with ideal conditions for their summer growth cycle”.

Despite this, Boutenac’s terroir is about more than Thézan molasse; some soils are much older. Also, the origin of the molasse was long a subject of debate before being definitively ascribed to the filling of a rift valley, which had formed at the foot of the Corbières mountain range, by pebbles swept downhill by the ebb and flow of rivers twelve million years or so ago. Both are good reasons to return to the starting point and follow the course of geological time.

In the beginning was the interplay of the sea

Having said that, it is challenging for any lay person not to get led astray in the account told by the specialists, especially when it runs from the Jurassic period to the present day, thereby covering an incredible 203 million years or so (MY)...

So when wine-loving geologist Philippe Fauré painstakingly unravels the score of this symphony of elements, the seeds are sown for a plan to convert these millions of years into as many seconds, thereby wrapping up the storyboard for a clip lasting three minutes and twenty-three seconds that is designed to make the symphony’s movements more tangible. And as we will see, the story unfolds at a disconcerting rate.

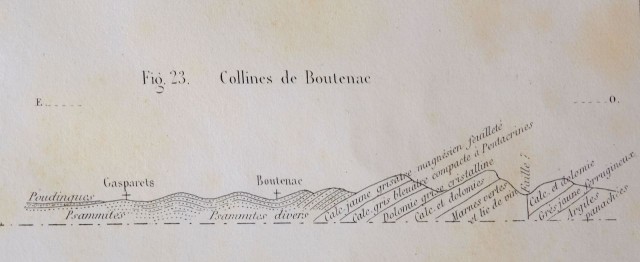

The introduction is more akin to a ‘hovering’ movement: three seconds dusted with red clay, deposited at the bottom of some lagoon on the edge of the ocean emerging between Africa and Eurasia, the Tethys Ocean. Then come eleven seconds of paddling in a vast expanse of very shallow water, or “coastal benches still far from the open sea, lined with stromatolite algae” where the dinosaurs roam. At this point, the dolomites and limestone, which form the foundations of the Pinada, are deposited. Present-day evidence of this can be found in the Lauze clearing, above Ferrals.

After this, sedimentation pauses for one minute forty, during which erosion has plenty of time to gnaw away at the Jurassic soils. Bauxite that has escaped from the red crust of the laterite of the neighbouring emerged continent (the future Massif Central) fills the hollows. It takes a highly trained eye to spot the last fragments of it today, topping the cliffs over Romanis valley.

As we near the middle of the clip, which has been haunting up until that point, the tectonics finally send out a muffled rumble: the Hispanic plate to the South and the Eurasian plate to the North begin to move apart, and an arm of the sea gradually opens up in an East-West direction.

At 1 minute 43, the Languedoc corridor (-103 MY) is etched out: the sea reaches as far North as present-day Provence. For 25 seconds, in this arm of the sea, “red-brown siliceous sandstone interspersed with red marl and quartz pebble puddingstone are deposited on top of the eroded Jurassic terrain”. This is the “Pinada sandstone”. The era is now the Upper Cretaceous (-90 MY) and the Pinada is bulking up in the East, at the southern tip of the Languedoc corridor. It takes just 5 seconds to lay the foundations of the Pech Tenarel; establishing the framework of the Fontfroide hill range will take 20 seconds.

Tectonics enter the fray

At 2 minutes 13, the score is magnified: the Iberian and Eurasian plates start to move closer together, and the maritime area closes up from East to West. “A new corridor then forms, to the North of the future Pyrenean mountain range opening onto the Bay of Biscay, and collects continental sediment then marine silt in the form of grey marl which only reaches Boutenac at the eastern end of the corridor”, where Saint-Laurent-de-la-Cabrerisse is now situated.

At 2 minutes 35, for ten seconds (-48-38 MY), the immediate erosion of the lower hill ranges deposits Carcassonne molasse washed down by rivers and “combining alternate layers of sandstone, conglomerate and silt, with some lacustrine limestone” in this corridor. At the easternmost point of this drum roll in the Corbières, Fabrezan, Ferrals and Villerouge then become home to the layers of large pebbles which will form the plateaux of Roudeille, Pech Fourcat and Garrigue Plane.

At 2 min 46, the Eocene Epoch comes to an end, and the tempo gains momentum again for 4 seconds. The Pyrenean fold increases as the plates close in: the ridges and troughs are superseded by lateral shifts, thrusts and overlaps. “The Pinada is hit by a succession of North-South folds”, explains Philippe Fauré. “The iconic Barrylongue anticline contracts, sinks and then breaks. The entire Jurassic hill range ends up detaching itself until it overlaps the younger Tertiary layers located between Ferrals and Les Palais to the West”.

At 2 min 55, a new twist in the story occurs: the pressure is released, and “a continental extension causes the collapse of the Pyrenean mountain range” leading to the formation of the Gulf of Lions (-28 MY). Eight seconds elapse before a boulder breaks away from the coast and drifts away; a further five seconds and the boulder, now in two parts, settles offshore: enter Corsica and Sardinia. The sea moves inland but does not reach Boutenac – it’s as if the Pinada is fighting off all the upheavals around it.

As the continental extension continues and we get to 3 min 11, two rift valleys are formed on either side of this block of limestone and sandstone, as if to bless the Pinada’s protection of sovereign power: one near Camplong-Fabrezan, the other towards Thézan. The latter in particular, all the way along the fault formed South of the Pinada, will witness the accumulation of rocks carried by mountain streams flowing down from the Corbières during the Miocene - “siliceous sandstone, conglomerates, clay, plus some wetland limestone, in variable proportions”.

This great sedimentary mixture, between Saint-Laurent and Gasparets, is Thézan molasse. In the clip, this ‘rock'n'roll’ finale takes about ten seconds (between -12 and -2 MY), like a closing riff (1).

At 3 min 20, there are still three seconds of reverberation left; the sandstone scree of the Pinada is delicately woven into the Miocene molasse between Fontsainte and Les Ollieux. The stage is now set and the winegrowers' choir can take up position.

The blessing of INAO

In 2004, the experts commissioned by Inao to demarcate the area of the Corbières-Boutenac appellation went through this complex terroir with a fine-tooth comb, one plot after another. To select plots, they based their choices on reliable criteria, favouring “loose detritic soils over great depths, displaying a certain proportion of coarse elements (pebbles or stones) but also a fine fraction establishing a propensity to retain water. This ensures a sufficient supply of water and an optimal exchange capacity between excessive fertility and notable deficiencies in macro or trace elements essential for balanced mineral nutrition at the depth tapped into by a powerful and branched root system”.

In this respect, as mentioned before, Thézan molasse (between 15 and 3 million years old), but also Carcassonne molasse, with its large rounded pebbles, 38 to 48 million years old, seemed to them to offer this “harmonious balance between stoniness and fine fraction providing the vine with ideal conditions to ensure its summer growth cycle”. Other soils, however, found favour with them. These include much more ancient outcrops of dolomitic limestone weathered over time in fairly large thicknesses to the North of the Pinada. At the other end of the hill range, there are some plots mixing “quartz and Lydian conglomerates, fine or coarse sandstone, sometimes alternating with marly beds, conducive to vine growing when they have the right ratio of earth and stones”. But there are also a few plots on limestone with relatively deep soils or on sandstone on the hillsides South of Thézan...

Ultimately, the Corbières-Boutenac AOC area delineated in 2005 stretched over 2,668 hectares embracing ten localities, slightly over a quarter of which is within the boundaries of the village of Boutenac. -•

(1) ‘Is it a musical riff or rift?” asks Philippe Fauré. “This could be an interesting play on words: the rift is the ultimate stage of the extension. The rift formed in the Gulf of Lions is responsible for the Thézan rift valley, and for the Corsica-Sardinia block migration… So it is also a decisive rift!”

The influence of sandstone on the wines

In 1897, the oenologist Lucien Sémichon, the first to attempt to characterise the wines of the Lower Corbières, considered that “a certain number of the wines of this region possess a particular bouquet stemming from the sandstone soils of the Cretaceous period”.

In the 1980s, the agronomist Jean-Claude Jacquinet noted for his part that:

“The presence of sandstone is a key element in the freshness of Boutenac wines. This is due to one main reason: unlike limestone soils, which have lots of cracks, sandstone promotes water retention in the soil”.

“It all depends on the nature of the sandstone”, clarifies soil scientist Stéphane Follain. “Generally speaking, sandstone formations have low water resources. Conversely, sandstone-dominant formations - either colluvial or alluvial - have higher water resources. In this case, the sandstone is not local, it has been transported and has melded with other materials on contact”.

This can be seen in the molasse located in the Boutenac area. Winegrower Jean-Marc Reulet can testify to this: “In places where you find a mixture of all soil origins, with depth and a significant proportion of sand (of sandstone and sometimes wind origin) the water supply is the most regular. Sandstone soils where the bedrock is exposed, on the other hand, are sensitive to drought. Sand not only promotes percolation, it is also a great ally on the surface where it slows down evaporation. For us, this is as important as rainfall or water retention capacity”.

“Sandy textures are less conducive to the spread of pathogens, so organic vineyard management is made easier”, comments Stéphane Follain. “And sandstone sands, which are usually acidic, prevent the emergence of weeds and therefore competition for water”, adds Jean-Marc Reulet.

Oenologist Marc Dubernet establishes a link between the freshness in the wines and the acidity of certain soils, “due to the occurrence of sandstone”.

In the shadow of the pebbles and large stones, generally considered as the primary cause of drive in the wines, could the mixture of sandstone and clay be Cru Boutenac’s secret weapon? Could it be the source of the elegance of its wines, of the “caressing edge” and “subtle, low-key nobility” that Marc Dubernet invariably recognises in them?

“That element of mystery is the sign of a great wine... It's fascinating!” concludes Stéphane Follain.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.