Winemaking in Boutenac (1/2)

Carbonic maceration – the key to recognition

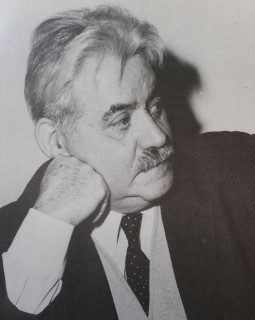

Michel Flanzy began experimenting with carbonic maceration in 1934 in Narbonne, but it was not until nearly 40 years later that the technique skyrocketed in popularity - in Boutenac in particular.

In 1872, Louis Pasteur claimed “it would be interesting to find out the difference in quality between two wines where, in one case the grapes were fully crushed, and in the other, most of them were whole, as occurs with an ordinary harvest”. Michel Flanzy, director of the Narbonne wine research centre, was unaware of Pasteur’s suggestion, but he would become the first person to conduct the experiment in 1934.

At the outset, following storage trials conducted with apples at the start of the 1930s in England, fresh grapes were stored in an atmosphere filled with carbon dioxide at the Gabarrou brothers’ Glacière Narbonnaise. The experiment was unsuccessful but the chilled grapes, once turned into wine, produced some surprising results. Michel Flanzy then came up with the idea of fermenting destemmed and crushed Aramon grapes and at the same time, uncrushed grapes in an oxygen-free tank.

The comparative tasting he organised in the February following the harvest produced striking results. Michel Flanzy described them in an article that was published soon after by the Revue de Viticulture: “For a start, the wine has a brighter colour, but more importantly it is remarkably mellow with a delicious fragrance, making it an altogether new wine, far superior to the wines generally produced. None of the fifteen professional tasters was willing to believe the wine was made from Aramon and all of them thought the wine had been given an artificial bouquet”.

But as surprising as it may seem, especially for an Aramon wine usually considered to be insipid when grown on the plains surrounding Narbonne, “this remarkable fragrance, recalling a vine in full bloom”, was not, for Michel Flanzy, the most worthwhile aspect of carbonic maceration (the name he gave the technique in 1940). In his opinion, it was the development of wine’s natural immunity (against oxidation and pathogens) that constituted its primary contribution. It reined in the amount of SO2, and as Michel Flanzy wrote – “the major flaw of SO2 is to very significantly reduce a wine’s vitality”.

A lukewarm response before the war

Despite these persuasive arguments, carbonic maceration was still a long way off immediate uptake by prominent southern producers. Flanzy missed the mark, and even became controversial, and was forced to bide his time. Carbonic maceration would not recruit its first converts until the 1950s, in Beaujolais, Châteauneuf-du-Pape with Dr Dufays at Château de Nalys, Libourne and then in the Gaillac area with Henri-Jean Dubernet, the then director of the Labastide-Levis co-operative winery.

The top Bordeaux oenologists Jean Ribéreau-Gayon and Emile Peynaud, who were great advocates of destemming and crushing, turned their noses up at the technique. “Winemaking using carbonic maceration delivers wines with particular, pleasant aroma characters, albeit quite far removed from those of their original grape varieties, along with more suppleness due to a reduction in tannin and acid content”, claimed Emile Peynaud. “It modifies the style of traditional wines”. For the Bordeaux oenologist, it was frankly not recommendable for fine wines.

Basing his opinion on wines by Philippe Dufays in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, agronomist Pierre Charnay plainly did not share the same thoughts in 1958: “The floral or exotic bouquets quite quickly disappear to make way for the local style, but a style that is considerably improved upon, a lot finer with a richer bouquet”.

Back in Narbonne, Michel Flanzy resumed his trials in the 1960s, thanks to the creation by Inra (National Institute for Agronomic Research) of the experimental Pech-Rouge estate in Gruissan in 1956.

An element of mystery

This time around, recognition would not be long in coming. Partnering in 1969 with Henri Demolombe, the creator of a wine laboratory in Narbonne, Jean-Henri Dubernet would become the proponent of carbonic maceration in Corbières and Minervois. “This method of winemaking became a very important weapon for allowing Carignan to thrive. Up until that point, the varietal’s hallmark features were robust tannins and a lack of aromatic expression”, recalls Marc Dubernet, who joined his father in 1974. “The rustic Carignan varietal would gain a pedigree and gentleness through carbonic maceration”.

“This is particularly true when Carignan is harvested at 11-12°, fairly under-ripe, which was more often than not the case at the time”, points out Jean-Marc Reulet of Domaine Hauterive-le-Haut. “Carbonic maceration causes some of the malic acid to be consumed, which translates to lower acidity in the finished wine, and therefore rounder wines”, explains Marc Dubernet. “The tannins are softer, though we are unable to analyse why from a chemical perspective. An element of mystery remains, but at the end of the day, it allowed us to move forward quicker. Joseph Saignes, then the largest negociant trading in Narbonne wines, very soon required all wines to be made using carbonic maceration under pressure from wine merchant Nicolas”. “Nicolas used to sell the wines under the Chaintreuil brand name”, remembers Yves Laboucarié, an early adopter of this winemaking technique at Domaine de Fontsainte.

Such keen interest was not an isolated case. In February 1971, 250 industry members from eight countries took part in a congress on carbonic maceration held in Avignon. Two years later, Michel Flanzy supervised the first book on carbonic maceration, which rapidly sold out. Subsequently, “the extension of winemaking using carbonic maceration to various French and foreign wine regions skyrocketed”, wrote Claude Flanzy in a book paying tribute to his father in 1998.

Forty years would pass between Michel Flanzy’s initial trials and the surge of carbonic maceration in the Corbières. But from then on, it would rapidly play a predominant role in wineries, and have a decisive impact on recognition of the Boutenac appellation in 2005.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.